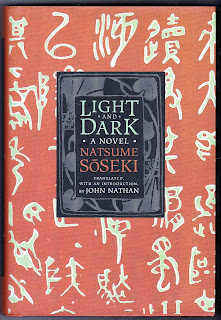

Light and Dark is a novel to be best read with the phone off the hook and the internet left unconnected, in this new translation by John Nathan it comes in a page shy of 420, originally published in 188 instalments in 1916 of the Tokyo and Osaka editions of the Asahi Shinbun, Sōseki passed away before being able to finish it, although on his desk was left the blank paper with the number for instalment number 189 written in and waiting to be filled. As with all unfinished novels the mystery hangs over what was meant to be, reading the book feels slightly akin of finding oneself within a confined space but with the added dimension of the door being left open at one end. John Nathan in his introduction points out that in it's incompleteness it is complete, everything we need to know is there in what we have, perhaps it brings to mind the conundrum that faces all artists of when is their painting actually complete?. Perhaps it could also be said that with Light and Dark you could approach a reading of it with these two perspectives in mind, one of it being presented as a novel and secondly of the original appearing in instalments, of the events arriving sequentially. Columbia University Press have presented a fantastically produced edition of the book with the original illustrations from Natori Shunsen, a master of yakusha-e, heading each of the numbered instalments and when slipping the book's jacket off, the hardcover comes with an illustrated embossed cover and the page cut comes deckle edged, it's a handsomely produced edition to behold.

At the centre of Light and Dark is Tsuda and O'Nobu, newly wedded, Tsuda being slightly the eldest, they are still dependant financially on monthly contributions from Tsuda's father in Kyoto, which at the beginning of the novel begins to cease being paid, perhaps this is a possible punishment for past deeds?. Reading Light and Dark is no small commitment on the reader's behalf, it is a substantial read, being more lengthy than I Am A Cat, whilst reading invariably the mind turns to contemplate Sōseki writing it in his state of deteriorating health and of also noting at the same time some aspects and familiar motifs associated with the author that occur within the text, in one scene a visit to London is recalled,and dotted through the book are occasional references to Chinese poetry and proverbs, in another brief and fleeting scene the ethics of Naturalism are shown to be ineffectual, added to this Tsuda suffers from stomach lesions for which he his operated upon. Much of the drama of the novel is mainly passed through few characters, the character that appears to receive most of the attention and study is Tsuda who spends most of the novel recuperating from his operation, whilst in bed he receives visits from among others Kobayashi, who is imminently departing for Korea, Kobayashi is a man, although they may have shared a friendship in the past, is in ways the antithesis of Tsuda, towards the end of the book there is a showdown between the two where the men vent their scorn toward each other and their different senses of morality, throughout the book Kobayashi has held the upper hand to Tsuda's assumed respectability as he knows an episode from Tsuda's past which he threatens to relate to O'Nobu, it comes down to a question of money, where again Kobayashi is again unable to resist from exacerbating and demonstrating Tsuda's moral bereftness, it could be said that Kobayashi is testing out elements of the moral pretensions of the day, it's left to us whose right holds out. Throughout the book the reader's sense of empathy shifts between Tsuda and O'Nobu, (as it does more subtly between Tsuda and Kobayashi), a subplot earlier in the book is the possibility of a miai in the family and this provokes O'Nobu to revaluate her marriage compatibility with Tsuda, who by turns we get the impression has had his hand slightly forced into the marriage, the interplay of these considerations on their parts it could be said is back dropped by the world of stifled conventions that have no interest in real or true desires.

Across its panoramic vision it could be said that Light and Dark is a novel of varying contrasts, the title is one that rather being represented in any one scene, (among these ones which we are left with), but one that is hinted to in a number of scenes of one being thematic, throughout these we're reminded of Sōseki's interest in Buddhist thinking and of life's continual dualism, as seen in Uncle Fujii's theories on male and female relationships, in which moments of enlightenment are reached and constitute a larger circle of harmony then disharmony, rather pointedly O'Nobu criticizes Fujii by admonishing him, 'You're so long winded Uncle'. The secret in Tsuda's past withheld from O'Nobu is also something described as being something kept in the dark, these contrasts can also be seen when Madam Yoshikawa visits Tsuda and discussing Kiyoko-san she asks him 'I imagine you still have feelings for Kiyoko-san?', he replies with 'Do I appear to have feelings?' Madam Yoshikawa replies with, 'For just that reason. Because they don't appear'. Reading Sōseki there's always a sense of drifting between worlds, Meiji into Taisho, which also enables to step out and transcend the age of their setting. An aspect that imbues his work is a sense of the organic that filters through, there's almost an utter lack of pretension in his characters which impresses them and their predicaments into the reader's sphere of empathy, and although he was tackling contemporary issues of his day there's a feeling in his writing that despite all being impermanent he sees things from the fixed point of the heart, through all it's wanderings, be they through the labyrinth of corridors of a distant onsen, of the opposing predicaments of love and then to end on the enigma of a smile.

Light and Dark at Columbia University Press

At the centre of Light and Dark is Tsuda and O'Nobu, newly wedded, Tsuda being slightly the eldest, they are still dependant financially on monthly contributions from Tsuda's father in Kyoto, which at the beginning of the novel begins to cease being paid, perhaps this is a possible punishment for past deeds?. Reading Light and Dark is no small commitment on the reader's behalf, it is a substantial read, being more lengthy than I Am A Cat, whilst reading invariably the mind turns to contemplate Sōseki writing it in his state of deteriorating health and of also noting at the same time some aspects and familiar motifs associated with the author that occur within the text, in one scene a visit to London is recalled,and dotted through the book are occasional references to Chinese poetry and proverbs, in another brief and fleeting scene the ethics of Naturalism are shown to be ineffectual, added to this Tsuda suffers from stomach lesions for which he his operated upon. Much of the drama of the novel is mainly passed through few characters, the character that appears to receive most of the attention and study is Tsuda who spends most of the novel recuperating from his operation, whilst in bed he receives visits from among others Kobayashi, who is imminently departing for Korea, Kobayashi is a man, although they may have shared a friendship in the past, is in ways the antithesis of Tsuda, towards the end of the book there is a showdown between the two where the men vent their scorn toward each other and their different senses of morality, throughout the book Kobayashi has held the upper hand to Tsuda's assumed respectability as he knows an episode from Tsuda's past which he threatens to relate to O'Nobu, it comes down to a question of money, where again Kobayashi is again unable to resist from exacerbating and demonstrating Tsuda's moral bereftness, it could be said that Kobayashi is testing out elements of the moral pretensions of the day, it's left to us whose right holds out. Throughout the book the reader's sense of empathy shifts between Tsuda and O'Nobu, (as it does more subtly between Tsuda and Kobayashi), a subplot earlier in the book is the possibility of a miai in the family and this provokes O'Nobu to revaluate her marriage compatibility with Tsuda, who by turns we get the impression has had his hand slightly forced into the marriage, the interplay of these considerations on their parts it could be said is back dropped by the world of stifled conventions that have no interest in real or true desires.

Across its panoramic vision it could be said that Light and Dark is a novel of varying contrasts, the title is one that rather being represented in any one scene, (among these ones which we are left with), but one that is hinted to in a number of scenes of one being thematic, throughout these we're reminded of Sōseki's interest in Buddhist thinking and of life's continual dualism, as seen in Uncle Fujii's theories on male and female relationships, in which moments of enlightenment are reached and constitute a larger circle of harmony then disharmony, rather pointedly O'Nobu criticizes Fujii by admonishing him, 'You're so long winded Uncle'. The secret in Tsuda's past withheld from O'Nobu is also something described as being something kept in the dark, these contrasts can also be seen when Madam Yoshikawa visits Tsuda and discussing Kiyoko-san she asks him 'I imagine you still have feelings for Kiyoko-san?', he replies with 'Do I appear to have feelings?' Madam Yoshikawa replies with, 'For just that reason. Because they don't appear'. Reading Sōseki there's always a sense of drifting between worlds, Meiji into Taisho, which also enables to step out and transcend the age of their setting. An aspect that imbues his work is a sense of the organic that filters through, there's almost an utter lack of pretension in his characters which impresses them and their predicaments into the reader's sphere of empathy, and although he was tackling contemporary issues of his day there's a feeling in his writing that despite all being impermanent he sees things from the fixed point of the heart, through all it's wanderings, be they through the labyrinth of corridors of a distant onsen, of the opposing predicaments of love and then to end on the enigma of a smile.

Light and Dark at Columbia University Press

No comments:

Post a Comment